Sarajevo is a delightful and fascinating city; the people are friendly, the food is good, and it is very cheap. What is not to like? Its charms are a blend of the Hapsburg and the Ottoman, the Central European and the Oriental. There are some fine churches and some nice mosques, none of which have more than one minaret. In Istanbul, some have four minarets, and one even has six; but in this provincial backwater, things are on a more homely scale, and no less charming for that.

Sarajevo is also a city scarred by war. For over three years it was besieged by Serbian forces who shelled it remorselessly and damaged some of its finest buildings, starving and killing many of its inhabitants. Many of its buildings, including its neo-Moorish Hapsburg era Town Hall, have been rebuilt and restored. With some of the mosques, close examination reveals a degree of restoration that is regrettable, but perhaps was necessary: some have been rendered with a not very sympathetic coating, making them effective rebuilds rather than restorations. But still, most people would not be looking too closely. A great many buildings have not been restored at all, and still have facades pockmarked by shrapnel. Looking at the scarred buildings, one wonders about the scarred people and the scars of memory.

Sarajevo Canton’s Croat (or Catholic) population has decreased markedly since the war, and its Serb population has more or less disappeared, or rather moved away to a new city of the other side of the airport.

The journey here was extremely long (there are no motorways) and instructive. Leaving Serbia, my bus made its way through Republika Srpska, which is the ‘entity’ created by the Dayton Peace Accords, for which the Serbs in Bosnia fought the war. The bus deposited me in the new town of East Sarajevo, which is in the said republic. The invisible line dividing the two ‘entities’ is about 200 metres from the city centre of Sarajevo, but there is a world of difference between the two. Republika Srpska consists of a string of ghost towns, vaguely reminiscent of the Soviet bloc, circa 1970. By contrast Sarajevo is bustling, and, yes, happy. At Dayton, the Serbs got what they wanted, their own ‘entity’; but the moral of this story is that you should be careful what you wish for. The Serb victory has proven hollow.

Sarajevo has several excellent museums and exhibitions devoted to the conflict, lest it be forgotten. One such is Galerija 11/07/95 which commemorates the Srebrenica massacre which occurred on that date. It is just a collection of photographs with an accompanying commentary by the man who took them, but my goodness, its strength lies in the understated nature of some of the exhibits. Every picture tells a story, as they say, and this story is truly one that needs to be told again and again and never forgotten.

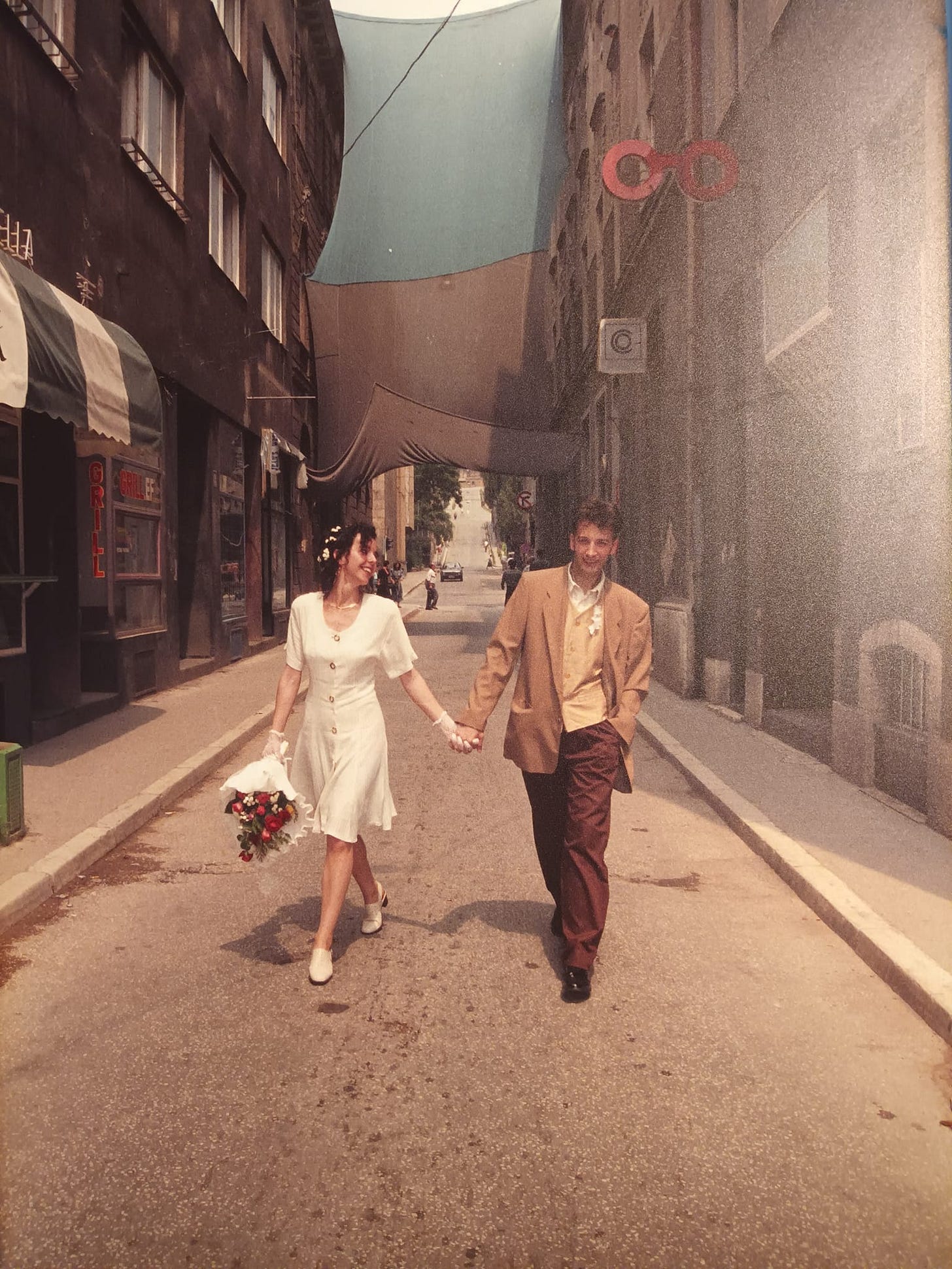

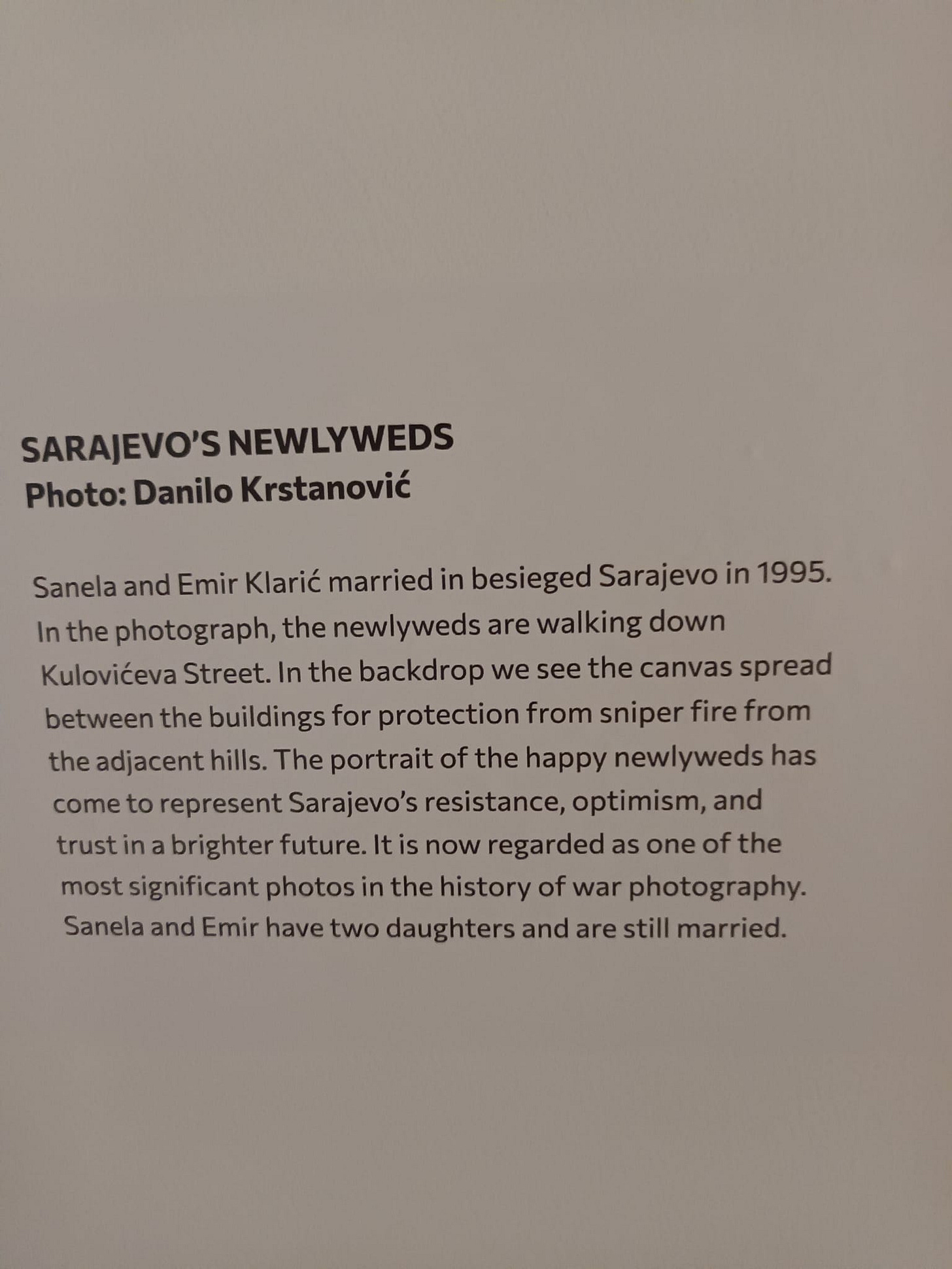

Further away, in the newer part of town, is the still war-damaged History Museum of Bosnia and Hercegovina, which has an exhibition about the break-up of Yugoslavia and the siege of Sarajevo. We have to some extent digested the horrors of the sieges of the Second World War, and we ‘know about’ Stalingrad and the fall of Berlin, but the siege of Sarajevo is still fresh, and the perpetrators of that siege are not repentant either and living just up the hill within sight of the city. The exhibition is, as they say, harrowing, and it cannot but be harrowing, but in all this suffering there is some hope. Have a look at this beautiful young couple:

Now read the caption:

They ‘are still married’. There is hope for humanity yet.

Years ago, I saw this poem on the tube in London, and the above photograph made me think of it again and look it up:

In Time of ‘The Breaking of Nations’

BY THOMAS HARDY

I

Only a man harrowing clods

In a slow silent walk

With an old horse that stumbles and nods

Half asleep as they stalk.

II

Only thin smoke without flame

From the heaps of couch-grass;

Yet this will go onward the same

Though Dynasties pass.

III

Yonder a maid and her wight

Come whispering by:

War’s annals will cloud into night

Ere their story die.