If you think that BBC I-Player is full of crime, then you would be right; this seems to indicate that programmes about crime are what we all want to watch. I certainly want to, and I have been devouring various box sets. Just recently I have been tackling Shetland, and a more recent offering from RTE called Kin. I recommend both, by the way, as they both entertain and enthral; though I have been watching, in addition, to try and understand just how they enthral and entertain. What tricks of the trade can be learned?

The first is a rather obvious one: have a very definite sense of place. Both do this superbly. Shetland is a beautiful background for any series, bleak, dramatic and a wonderful symphony of sea, land and sky. Lerwick looks rather attractive, which is something of a surprise. Moreover the island is a character in the story: it is a small, remote and isolated community, and everyone knows everyone else. There is an air of claustrophobia about the place, in spite of those immense skies. This creates a great setting for a murder mystery, when one remembers that all such stories benefit from unity of place. (Agatha Christie, the great craftsman that she was, was addicted to islands, snowed in trains, locked rooms and remote country houses.)

Kin is set in Dublin, but not as we know it. The drug dealing criminals live in a blingy set of houses, and Dublin is dreary, rainy and dark - quite literally so, as most of it seems to be filmed at night, or at best on very overcast days. This sure is noir, almost taken to extremes. It is claustrophobic, doom laden stuff. While Shetland makes you want to take the plane to Lerwick, Kin convinces you to cross Dublin off your bucket list. But as television drama it works.

Setting is the easy part; it is characters and plot that you really need to draw the viewer or reader in. In this Kin falls down rather badly. I am only a few episodes in, and already the main character is looking very much like Lady MacBeth, and I even spotted a submerged Shakespeare quote (‘what is done is done’). Moreover, in deciding on revenge, the Kinsella family have shown that they are not disciplined and not clever. This means they are not good at being criminal, so one wonders how they got as far as they clearly did. The writers are perhaps aware of this threadbare plot, because they have crammed in a lot of plotlines reminiscent of soap opera, and a rather annoying backstory: why did Michael kill his wife? Will he see his daughter again? Why was he having an affair with his sister-in-law? The answer to all these questions is a shrug of the shoulders. Who cares?

Shetland is much better in delivering character. There is something about the moody Douglas Henshall that mesmerises the viewer, and I really like Tosh, his sidekick. When one remembers how many cop shows I have seen, these two have something original about them. The characters in Kin are, well, we have all been there before, and we don’t need to go there again.

Attempting some self-criticism, I think my own work does well on setting. Sicily is it! I mean, where else? But Sicily is quite easy to ‘do’. Unlike Dublin or Shetland, where the food is one suspects rather ordinary, and never mentioned, in Sicily one has the food to talk about and create atmosphere (this is a very old trick) and one also has the weather, either variants on boiling hot, or the gracious cool of October. There is also the geography of the island, and the way Etna lowers over the city of Catania. What more could one want? What better setting could there be?

Character is more tricky. I have read and reread Mario Puzo so many times, and am a little shocked by how crude his characterisation can be, but he surely knew and carried off the essential trick in creating character in a fiction about criminals. The criminals have to be both nasty and likeable at the same time. I was very pleased when someone told me that Calogero was both a cold hearted psychopath and oddly likeable as well. After all, in any fiction about criminals, you have to be on the side of the criminal while all the time knowing how bad he really is.

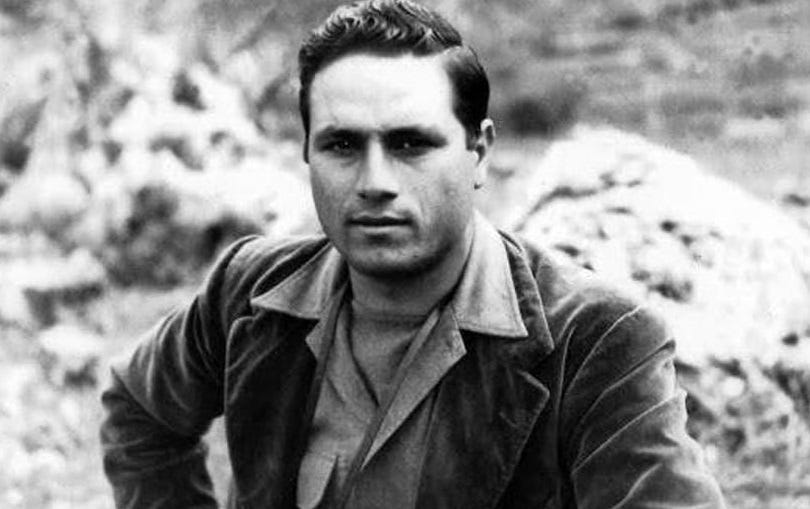

Consider the fons et origo of my inspiration, the outlaw Salvatore Giuliano. A mass murderer, he is still regarded as a romantic and popular hero in Sicily. People forget the bad, and love the good, or rather the perceived good, for there was no good there at all. But we only see what we want to see.

It used to be said that Agatha Christie’s huge success - and by the way, she is a superb author - was based on the fact that she delivered a black and white moral universe where the wicked are punished and the good rewarded, and where the truth will always out. It is true she delivers an intriguing puzzle and an elegant solution each and every time, but her universe is hardly moral, as in a good world the innocent and not so innocent would not get bumped off in such large numbers. That people take to murder so easily is a sign that there is something rotten in humanity. My guess, and it is only a guess, is that we love crime fiction not because we love justice, but because we are fascinated by evil, and we are, in a sense, voyeurs.