Running for another week or so, at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, is an exhibition of pictures by Letizia Battaglia. Entitled Life, Love and Death in Sicily, it certainly makes an impact, and I am not sorry I went. However…

Battaglia had an interesting life. She was born (in 1935) into a bourgeois family, we were told, and ran away from home at the age of sixteen, to marry her first and only husband, by whom she had three daughters. The marriage was not a great success (they divorced after 20 years or so) but it does show that people marrying young in Sicily is not unknown, which I find interesting. Battaglia started working as a reporter and took her first pictures to accompany stories in the papers. Gradually this sideline became her main thing, and she is famous for her stark black and white pictures that capture the terrible moments just after murders by the Mafia in the 1970’s. Sicily is a land of colour, but all newspapers were in back and white in those days, and the effect of these pictures is to drain Sicily of its colours, to make it look like the grim setting of a film noir, which, of course, to some extent, it is. Some of the pictures are very shocking, women weeping over corpses, dead bodies in cars; some are very actual, catching the moment in which some boss is arrested, or catching the strange interlude between the murder of a man and the magistrates coming to give permission for the body to be removed. To say it is dark is to understate the case. It is Gotham City. Battaglia in many ways created the popular idea of Sicily as a crime ridden society, a grim place, when, in reality, that is not the whole story. I suppose she wanted to draw attention to the obscured reality of the Mafia, and she certainly succeeded in doing that.

So much so, that they took umbrage. One of the more interesting exhibits is the letter they sent her, couched in polite and formal (though occasionally incorrect) Italian, which merely emphasises its threatening nature:

“Dearest Signora Letizia, You have not just taken the listed photographs, but you have also had them published. Therefore, we can advise you to leave Palermo at once, that is, to leave Palermo forever, because your sentence has already been passed. You, with your way of acting, have already caused us enough trouble [literally, bust our balls]. We have made ourselves clear. Do what you think best.”

Well, she did not leave Palermo, she called their bluff, and she died in her bed at a ripe old age in 2022.

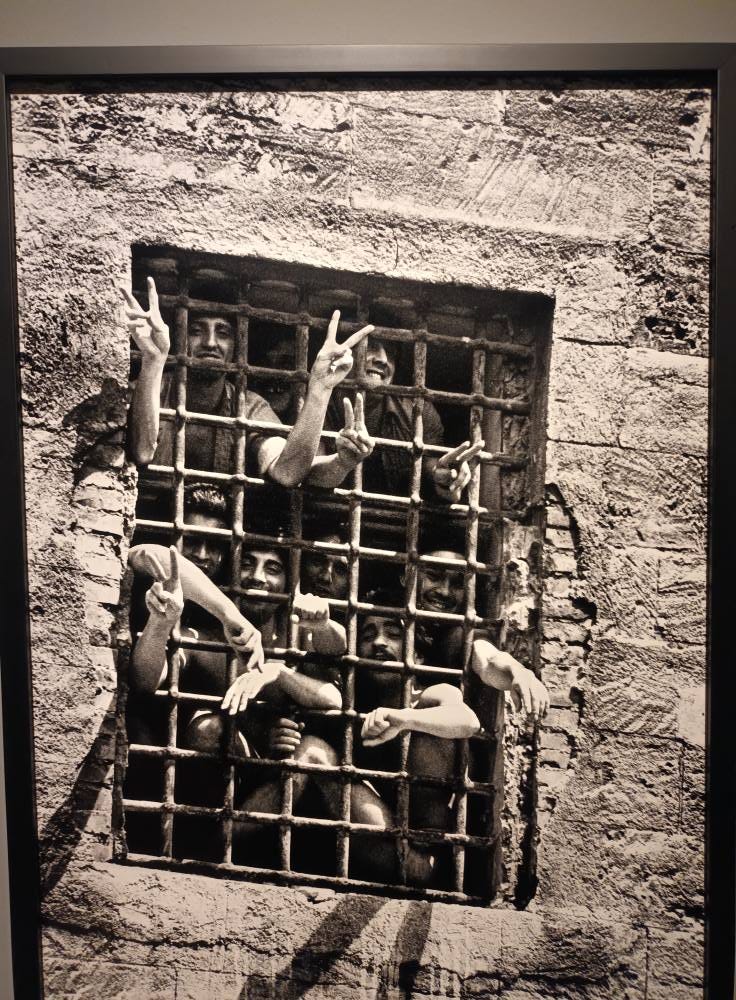

There was nothing in the exhibition saying you could not photograph the photographs (all of which are protected by copyright) so I took pictures of ones that particularly interested me. Here is a window in the grim Bourbon-era fortress that is the Ucciardone Prison, in the centre of Palermo, that I have written about before now. It tells you all you need to know about the prison management, I think. It also tells you about the way the criminals in the prison see themselves not as cowed or defeated, but as heroic. This picture underlines the difficulty of suppressing the Mafia; you can lock them up, but they still taunt you.

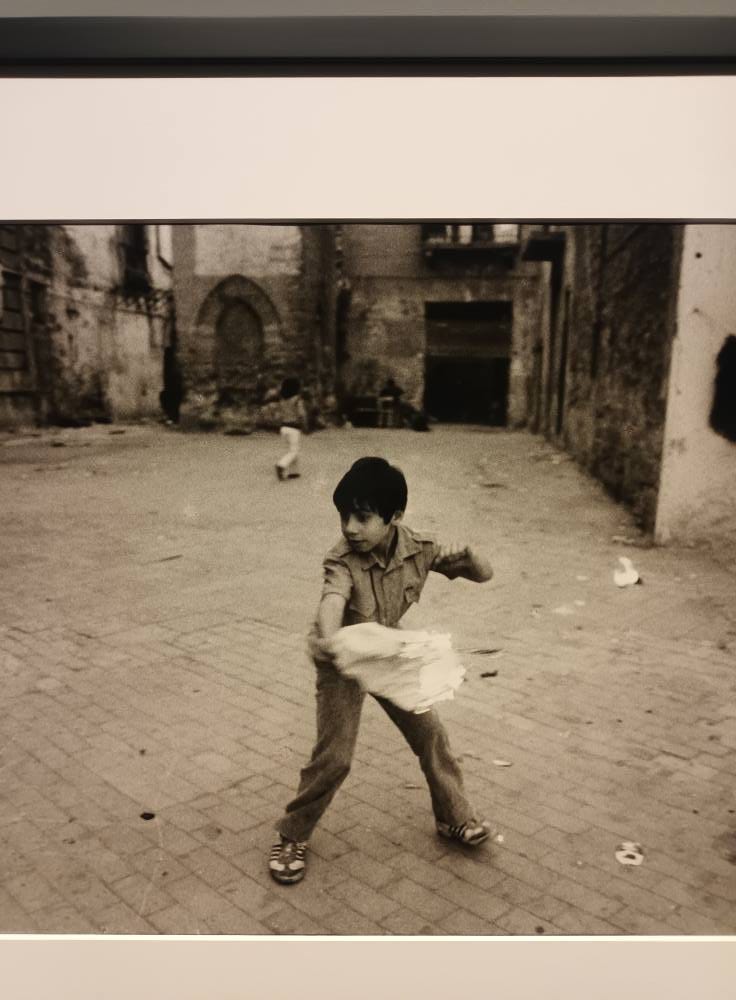

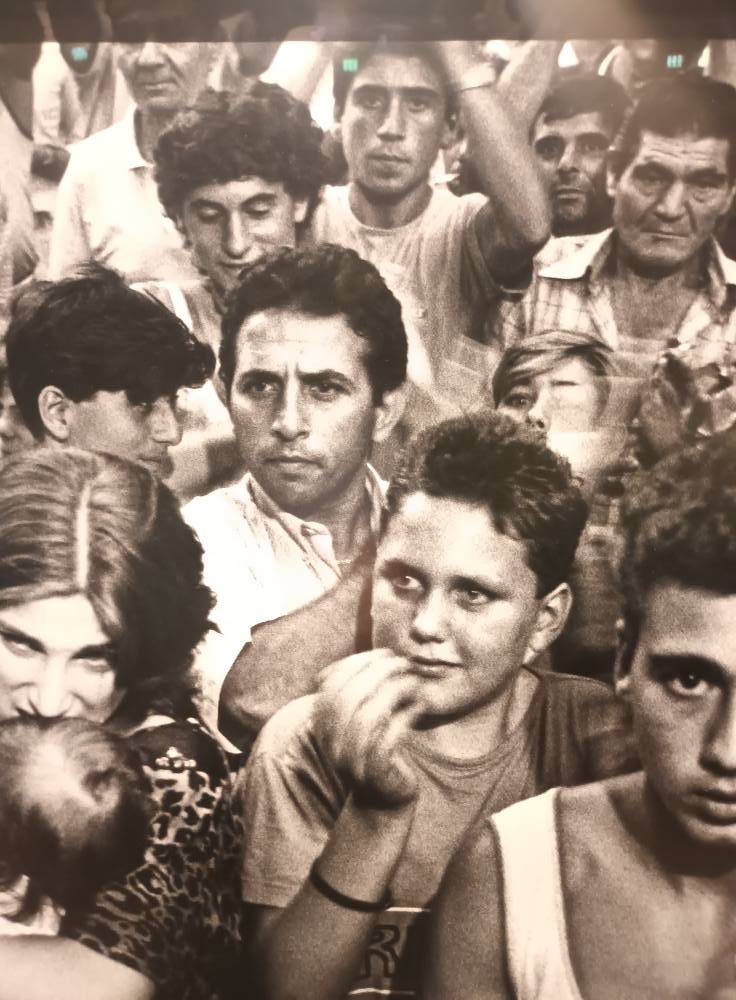

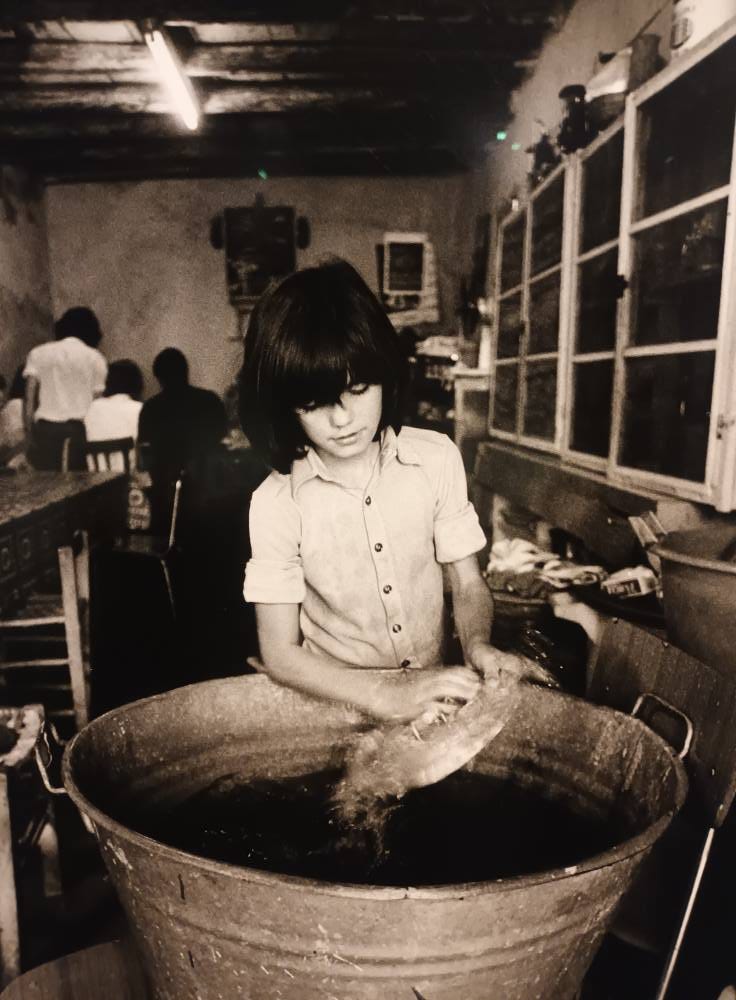

Then there are these stark reminders of poverty. These two photographs were taken in Borgo Vecchio, the district just outside the prison gates, which is the setting of part of the next book in my series, as yet untitled. Borgo Vecchio today is poor and shabby, but in the 1970’s, as these pictures convey, its poverty was palpable.

Battaglia’s pictures remind us of the deprivation of the south of Italy in general and Sicily and Palermo in particular. It has improved since the seventies, of course, but this is the real reason why organised crime flourishes. While many poor people never dream of breaking the law, some young men will bridle at the cruel yoke of poverty, especially poverty of opportunity, and this gives the Mafia its excuse, its claim to be a reaction to oppression rather than a perpetrator of it.

If you think I am exaggerating the degree of poverty, what about this picture of child labour in a dismal setting? It is not a domestic picture: this girl is employed in a restaurant of sorts, and the clientele are in the background. She can’t be more than nine or ten. This is a picture not just of poverty but of illegality, of child abuse, of a cruel and unfeeling world. In some ways, it sums Sicily up: cruel and unforgiving. No wonder men join the Mafia. If that was your daughter, wouldn’t you?

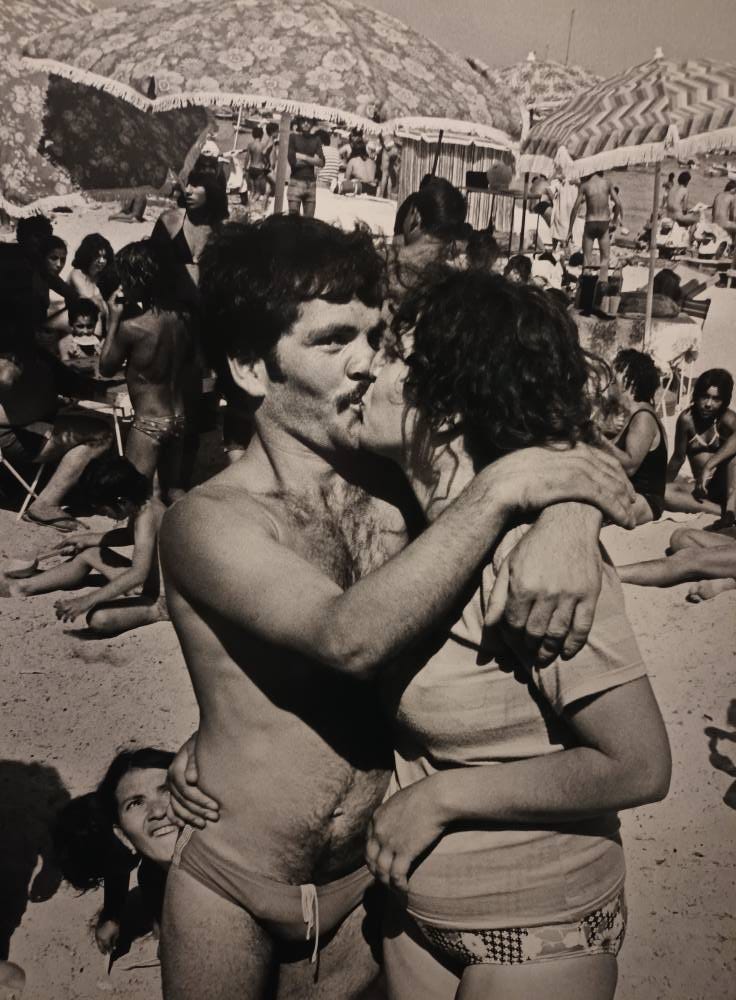

PS: At the top of the article I have put Battaglia’s most famous picture, that of a couple caught on Mondello beach, outside Palermo. Do look at it again. The man kissing the woman has one eye on the camera, and is happy to be photographed. He is visibly enjoying himself. The woman’s attention is fixed on him, which must be the reason, and he wants us to know it. Battaglia, the exhibition said, had a natural sympathy for women and children. One can see from this that she did, for one sympathises with the woman who does not seem to realise that she has been made into a male plaything - at least not yet.

I very much enjoyed the exhibition. For me it was quite personal. My father is from Palermo. He left in the late 70s to travel for working, ending up in the Uk. I spent every summer these as a youngster and still go regularly now to see family. Some of those images felt quite familiar. Things have changed for the better - but in some ways not so much. I think her photography cuts to some of complexities of the Sicilian psyche that remain today. The roots of widespread cynicism. Hostility to rules or order. An insular mindset that’s simultaneously frustrating but also often endearing.

Glad she made it until 2022