I have now arrived in Palermo where I am doing research. I am staying in a little flat right next to the Politeama, which is a magnificent building, best seen at night, and which is in the heart of the new town of Palermo, most of which is built in lo stile Umbertino, named after King Umberto, united Italy’s second monarch, who died in 1900, assassinated by an anarchist in Monza. Most Italian cities have a similar quarter. Readers may be familiar with Prati in Rome, for example. Palermo has some nice Umbertine buildings, though its chief glories are elsewhere.

The Politeama is best seen by night, because by day you notice just how terribly neglected the building is. It is a concert hall and theatre, but puts on but one show a week. Incidentally, the famous opera house (as seen in Godfather III) has nothing on at present, which is disappointing, but not surprising. The Catania opera was also silent when I was there, a sign of Italy’s cultural impoverishment, one fears.

While the Politeama is the heart of bourgeois Palermo, and the nearby Viale della Libertà is its smartest shopping avenue, which could, on a nice day, when you are not looking too hard, pass for the Champs Élysées, nearby not all is well. I am planning a book, and trying to locate where my characters should live. One I have placed in Piazza Ignazio Florio, named after the magnate whose wife was painted by Boldini, a pleasant enough square that is dominated by his statue.

But a short walk away is the port and the ferry terminal, where I am planning setting a crime, and turning north one comes to the slums of the Borgo Vecchio, which I discovered just by accident, on my way to the Ucciardone prison. It is surprising that a very poor district should be right next to a very expensive one. And it is very poor, and a little threatening for the fainthearted. There is evidence of bombing dating back to the last War, and ruined housing, along with the usual piles of stinking uncollected rubbish and lots of litter.

But in the heart of the quarter there is a statue of Padre Pio, Italy’s most popular saint. But even so, it is a heartbreakingly sad place.

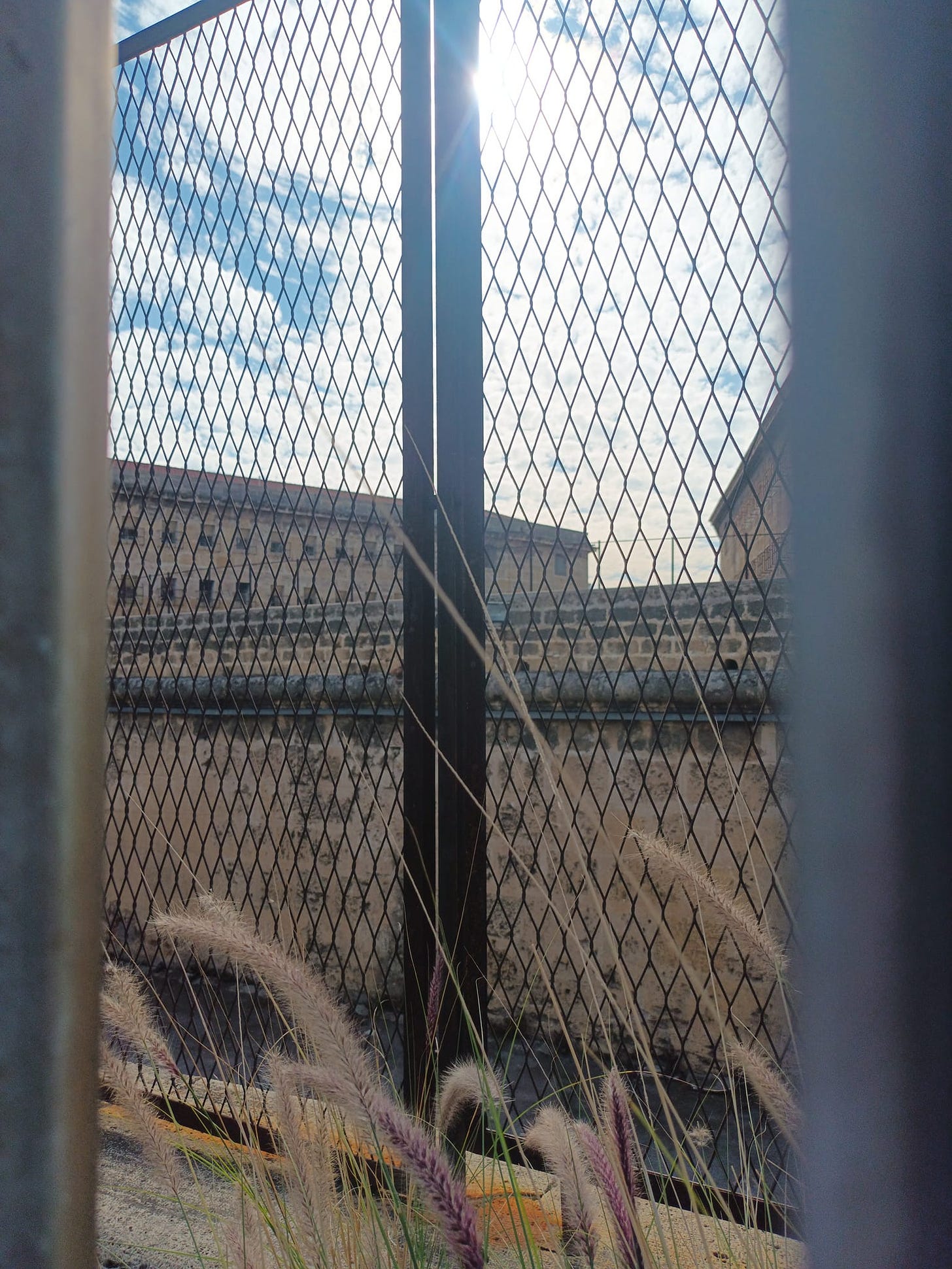

Just beyond Borgo Vecchio is Ucciardone, the famous prison where all the less important Mafiosi are held. It is very close to the port, and a busy road, as well as a railway tunnel, a place deprived of peace and quiet; the prison is a standard Victorian building on the panopticon model, that is, star shaped, like several British prisons. But what I had not appreciated was the fact that the prison is inside an old Bourbon fortress.

The actual prison itself is relatively hard to see, but I tried to take a few photographs, both of the outer wall and the interior.

To say that Ucciardone is grim is an understatement. It is inexpressibly depressing, the sort of thing that fires prison reformers to take up arms, I should imagine. You cannot see it in my photograph, but every single pane of glass in every window is broken. That struck me a simply awful. Ucciardone features in a future novel.

Next door to the prison proper is the fortified aula bunker, the ‘bunker courthouse’, where the Mafia trials are held, built for the famous maxi-trial of 1986. It was built to withstand missile attack. There are three separate iron fences to keep people away, hence photographing it is quite hard. It is now named after the heroic magistrates Falcone and Borsellino.

All of this is very grim, but I am glad I have seen it. One needs to be present, to catch the atmosphere that one hopes to convey on the page. Just a few minutes’ walk away from the aula bunker lies the English Garden (shut for restoration) and then you are back in the Viale della Libertà where the middle classes live.

Unlike most priests, I have never been inside a prison. As a slight claustrophobe, I shiver at the thought of the ‘inside’. But like most people, I believe the state has a right to imprison those guilty of serious crime, and that prisons should be places of rehabilitation, and I lament that they so infrequently are. I have heard bad things about some British prisons, but I am reassured that some are in the countryside and places where prisoners have fresh air and are not subject to the torture of being in the midst of a noisy, polluted and congested city. But Ucciardone gives the idea of being the worst sort of prison, even when just seen for the outside. It is a symbol of failure, and its Bourbon architecture underlines this. The Bourbons failed to contain their Sicilian problem, and the modern Italian Republic seems, despite the prison walls and the aula bunker, set on a path of failure too. Locking people up in such a place and administering justice from a bunker seem to be admissions of failure.

I mentioned that the less important Mafiosi end up in Ucciardone; the more important bosses are imprisoned far away and subjected to carcere duro, statutory harsher conditions. But the most important Mafiosi, one suspects, are never imprisoned at all.

An interesting read; thank you for the details.