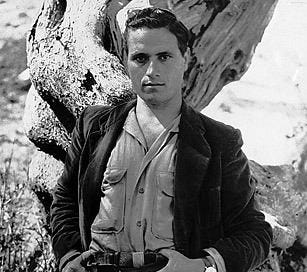

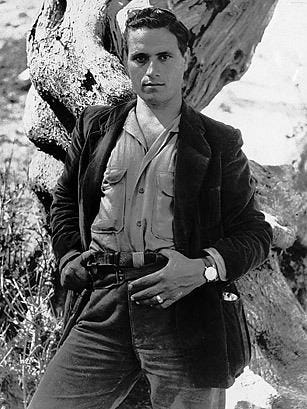

I gave a talk the other day at a Catholic Church in North London (many thanks to those who invited me, and to their kind parish priest). The subject was ‘Sicilian Beauty’, and I mainly focussed on the figure of Salvatore Giuliano, whom readers will know I am a little obsessed by, as are most Sicilians.

Giuliano honed his image very carefully, hence the famous posed photographs of the bandit king. Oddly, there don’t seen to be any pictures of him before that, as a boy for example, perhaps because he wasn’t important enough to care about his ‘image.’

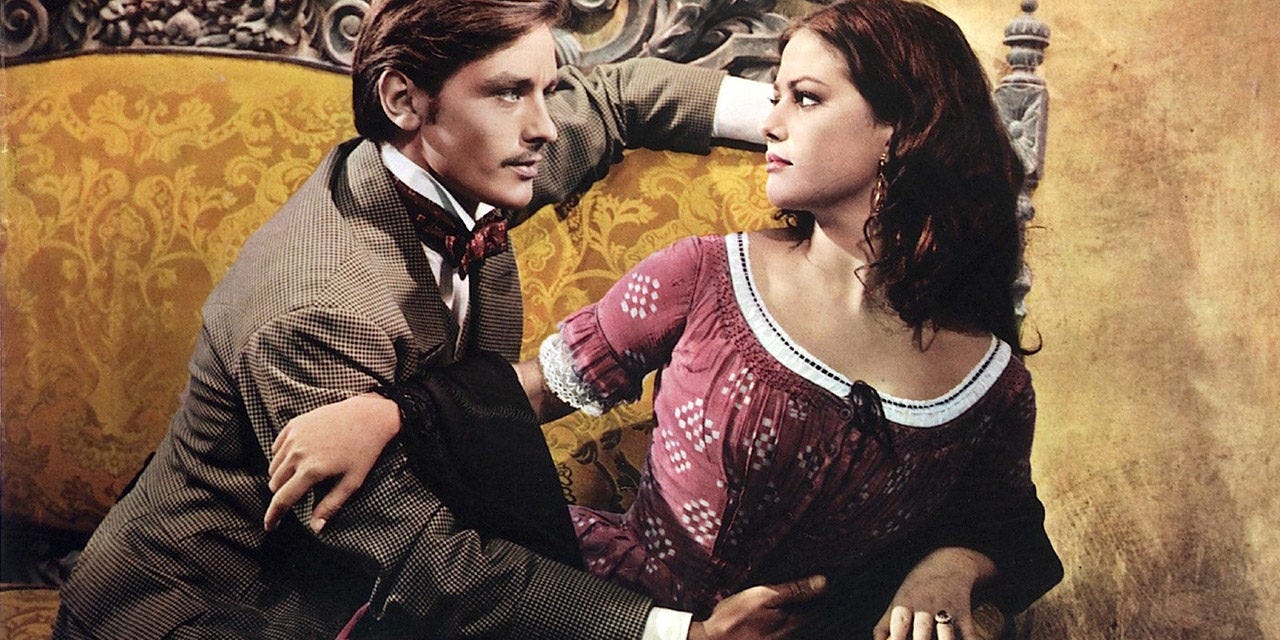

At the end of the talk I remarked that the book and film Il Gattopardo were probably the best summary of what makes Sicily the way it is, even though of course the book makes no mention of organised crime at all. But it does present several truths about the island.

First, a sense of decline, irreversible decline. Don Fabrizio, the hero, is part of a dying class. He lives in splendour, he is the owner of vast estates, but all this is coming to an end. But it is not just him, it is the whole of Sicily, which is drowning in a sense of tragic helplessness. The year is 1862, and Sicily is being incorporated into the new Kingdom of Italy, but nothing is going to change, and the rotting corpse in the garden in the first chapter is perhaps the real pointer of what lies ahead. Yes, everything is changing, but everything is only changing so it can stay the same.

Secondly, power and prestige are what really matters, but these things are invisible, and the power and prestige of the Salina family are seeping away, and the person who is emerging as the new man is don Calogero Sedara, the mayor of Donnafugata. The old must compromise with the new; don Calogero’s daughter can make a previously unthinkable marriage with the Prince’s nephew. This is a change, but once more one that enables everything to stay the same. It is also noteworthy that none of the prestige seems to be connected to economic productivity; though one hates to sound like a Marxist, the great men of Sicily produce no wealth, they merely consume it.

Thirdly, the state, the Kingdom of Italy, is illegitimate and based on a fraudulent series of plebiscites. Moreover, the state is the creation of foreigners: the Piedmontese, more French than Italian; Garibaldi, born in Nice; and the perfidious British like Palmerstone. Sicilians have no agency, and have not for a thousand years.

But the sense of hopelessness and helplessness co-exist with a profound beauty. Angelica Sedara, who is to marry Prince Tancredi, is of the most astonishing loveliness, as indeed is Tancredi. The landscape is beautiful and eternal, and even though so much of Sicily has been ruined, this beauty persists. The film is the masterwork of Visconti, and he, a decayed aristocrat himself, had a profound sense of the way beauty consoles us and at the same time torments us, reminding us of what we have, and what we have lost. No wonder that one of the Prince’s sons runs away from home to become an office clerk in London. Sometimes Sicilian beauty, and Sicilian decline, which manifest themselves at the same moment, are too much for a man to bear.

Now I want to see the film again. I watched it so many years ago. Long before I’d ever visited Sicily. Now that I live there and I am immersed in the history, I want to see the movie with fresh eyes.