There is a very good article about Sicily over at The Spectator by Sean Thomas, entitled ‘Sicily and the Slow Collapse of Civilisation’. Do please read it, as it makes great reading. His thesis is that Sicily, once a wonderful place, is fast decaying into a hellhole, and as Sicily is, the rest of the world will shortly be. He says:

“There is a darkness that grips Sicily, which says all that glory is in the past, and now there is only decline: and, worse, Sicily is merely the bellwether. What has afflicted Sicily is about to afflict the entire western world. Sicilian decline is our decline. Our future.”

He may well be right; he is certainly right about the horrors, for example, of the city of Agrigento, which I have seen for myself.

Thomas mentions the various high points of Sicilian history - the Arabs, the Normans, the time of Baroque splendour, but I wonder, by contrast, when was the lowest point of Sicilian history? And has Sicily somewhat revived since then?

Sicily was undoubtedly neglected by the rulers of the Kingdom of Naples; it was the ‘other’ place, poor, unvisited, similar to the way that Ireland was the ‘other’ island of Great Britain. Like Ireland it was dominated by landowners of vast estates, many of whom were absent, which was not a recipe for prosperity. Things changed, a bit, in the Napoleonic wars, in that the Bourbon rulers, under British protection, decamped to Palermo; it was there that the future Ferdinand II was born in 1810. In 1812, the Bourbons granted Sicily a liberal constitution, but, no sooner were they back in power in Naples, they suspended it. This must have infuriated the enlightened Sicilian nobles, and in 1848 there was a revolution in Sicily.

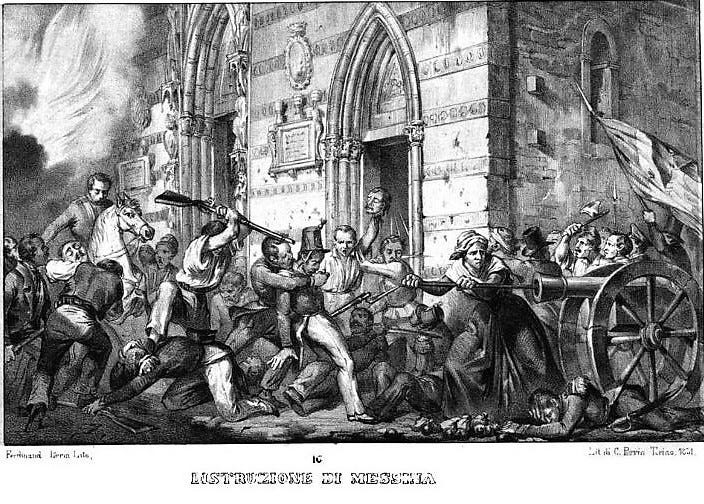

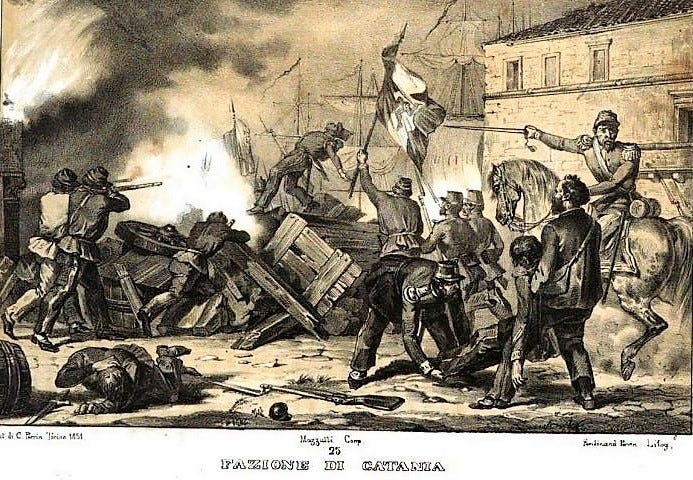

1848 was the year of Revolutions throughout Europe, but (and this surprised me) the Sicilian Revolution of 1848 was the first, breaking out on 12th January, and was initially highly successful. The previous constitution was restored, and the Bourbon army was expelled, with relatively little difficulty, though there was fierce fighting in Messina, in early September 1848. The Bourbon troops from Naples, trying to retake the island, carried out numerous atrocities, and the city was bombarded, which won for Ferdinand II the nickname ‘Re Bomba’. It was this incident, reminiscent of quite a bit of modern urban warfare, that destroyed not just swathes of Messina and lots of innocent civilian lives, but the reputation of the Bourbon monarchy, which became anathema in Britain and other liberal countries.

After the horrors of Messina, there was a truce, but in the spring of 1849, Filangeri, the Bourbon general, managed to reconquer the whole island. A liberal Sicily had lasted a mere 16 months, and the revolutionaries were forced to flee aboard, where they were welcomed as heroes. Ruggero Settimo, the head of the liberal government, fled to Malta.

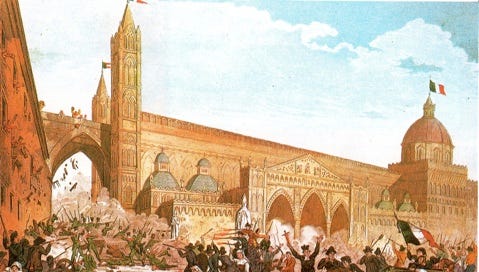

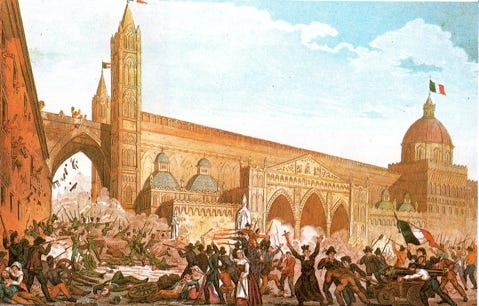

It was, of course, a pyrrhic victory. Sicily was subjected to what essentially was a fine to pay for the damage of the war, and occupied by foreign (in many cases Austrian) troops. But a mere eleven years later, Garibaldi landed at Marsala on 11th May 1860. By the end of the summer, it was over, despite the Bourbon government bombarding Palermo from the sea. Garibaldi is a great hero to many, but it needs to be pointed out that his expedition depended on the complicity of the Royal Navy, and owed its success on land to the incompetence and paucity of the Bourbon troops and the huge unpopularity of the government.

But after this glorious episode, the real tragedy began. Liberal Italy was a terrible disappointment to Sicily, and it must have seemed to the people of the island that they had swapped one absent tyrant for another, government from Naples replaced by government from Turin, then Florence, then finally Rome. The signs of this are perhaps best seen in the vast emigration from Sicily in the late 19th century, to Latin America, Britain and the United States, as well as France and Belgium, coupled with, of course, the rise of the Mafia, which was, at first, a direct response to the perceived tyranny of the North.

There have been three mightily waves of emigration from Italy. The first took off in 1880 and lasted to about 1920. the second was after the War, when conditions in Italy were extremely tough, and the winter of 1947-9 saw a famine; and finally there is a wave of emigration that is still going on. Years ago, I used to know lots of Italians in Britain who had arrived round about 1948, mainly to work in industry, and today too, as any parish priest will tell you, there are lots of young Italians working in Britain. And this is for one simple reason, the modern Italian state has failed to deliver.

One footnote. Emigration from Italy slowed during the Fascist period. This is rather an inconvenient truth, but there it is.

So, when was the worst period in Sicily’s history? I would say the aftermath of the Risorgimento. More than most Italians (bombardment of cities did not occur elsewhere, I think) the Sicilians suffered in the wars for independence, but they did not reap much reward. The despair must have been tangible. Consider this call to arms (my translation) from January 12th 1848:

Sicilians! The time for useless prayers has passed, along with useless protests, supplications, and peaceful demonstrations. Ferdinand has scorned them all, and we, a freeborn people, reduced to chains and poverty, are we to wait any longer to reclaim our legitimate rights? To arms, sons of Sicily! Our combined power can do everything. On 12th January 1848, at dawn, the glorious epoch of our regeneration will begin. Palermo will joyfully welcome as many armed Sicilians who will present themselves to support the common cause, to establish reform, political institutions in accord with the world’s progress, longed for by Europe, by Italy and by [Pope] Pius. Union, order, subordination to the commanders - respect for all property. Looting will be regarded as high treason and punished as such. Whoever has no weapon will be supplied with one. With our just principles, Heaven will bless out just undertaking. Sicilians, to arms!

Read it and weep. Risorgimento means ‘resurrection’. Sicilians are still waiting for the promises to be fulfilled.