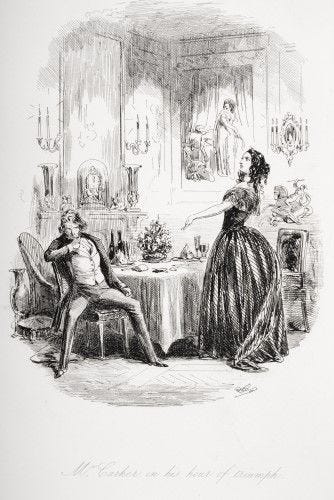

Charles Dickens only mentions Sicily once in his novels. You may remember in Dombey and Son, how Mr Carker the Manager runs off with Edith, his master’s wife, with the intention of their taking up residence in Sicily. However, the frigid, imperious and melodramatic Edith has other ideas, and while still in France tells Mr Carker that she has no intention of being his mistress:

'We meet and part to-night,' she said. 'You have fallen on Sicilian days and sensual rest, too soon. You might have cajoled, and fawned, and played your traitor's part, a little longer, and grown richer. You purchase your voluptuous retirement dear!' (Chapter 54.)

Mr Carker slinks off, feeling

[T]he dread of being hunted in a strange remote place, where the laws might not protect him - the novelty of the feeling that it was strange and remote, originating in his being left alone so suddenly amid the ruins of his plans - his greater dread of seeking refuge now, in Italy or in Sicily, where men might be hired to assassinate him, he thought, at any dark street corner…. (Chapter 55)

It is interesting that Dickens, writing in 1847, on the eve of the Year of Revolutions, sees Sicily as the natural refuge of adulterous and lascivious couples, as well as a place of disorder and lawlessness. He was, of course, completely right. In the 1840’s the Kingdom of the two Sicilies was notorious for brigandage, largely because it had no effective police force, nor any system of taxation to pay for one. Moreover, then, as now, English people could move to Italy and live in a manner immune to criticism, because Italians had no real expectations of how stranieri, particularly Protestant stranieri, should behave.

In Nancy Mitford’s unforgettable novel, Love in A Cold Climate, Polly Mondore marries the totally unsuitable ‘Boy’ Dougdale, who happens to be her former uncle by marriage and her mother’s lover; the two of them take refuge in Sicily. The marriage rapidly goes wrong. While Sicily boasts some ‘heavenly dukes’ there is very little else to do apart from water the geraniums (which stops them flowering, apparently), and Boy spends his time indulging his sexual tastes in other ways too.

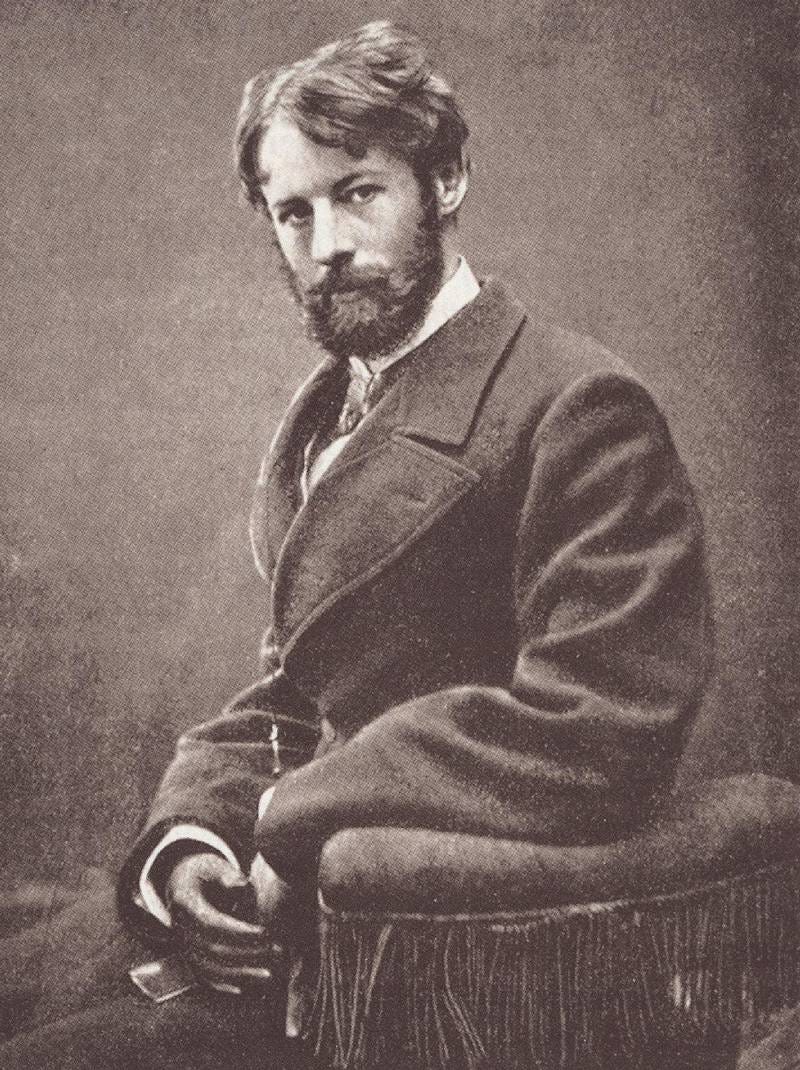

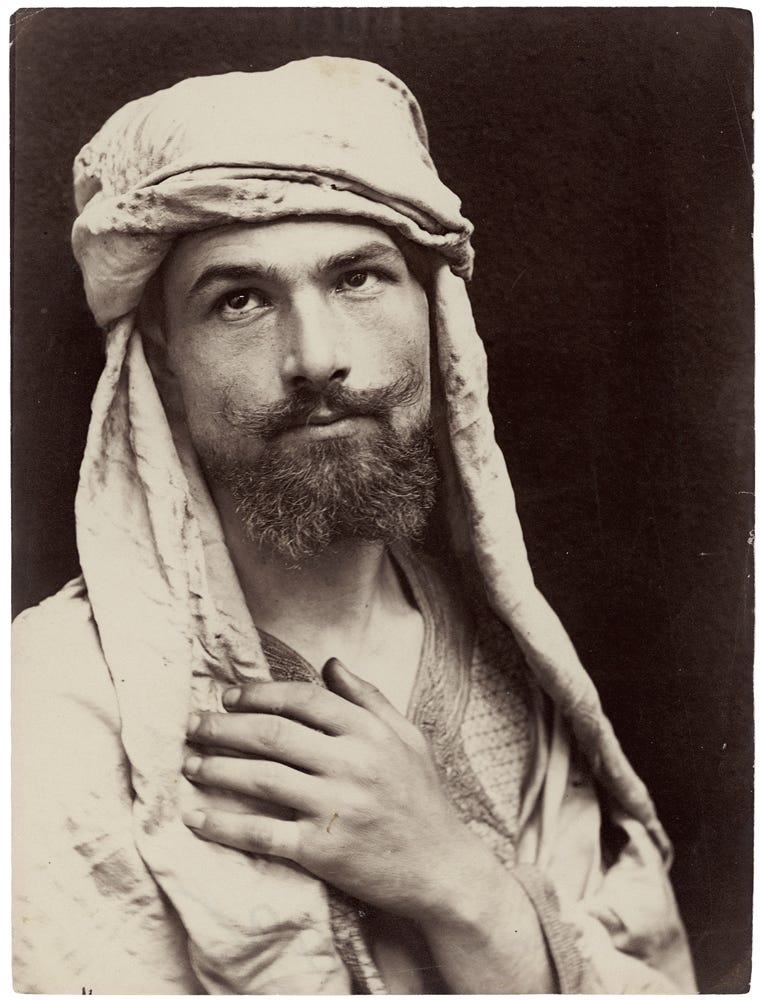

While the fictional Boy and Polly were resident in Sicily they would perhaps have met Baron von Gloeden, the celebrated photographer, who lived for over fifty years in Taormina, which was at that time developing into a tourist resort. The Baron (who was not a baron) made a substantial living from his art. It was only after his death in 1931 that the local Fascists confiscated his collection, condemned it as pornographic, and put his assistant and heir ‘Il Moro’ on trial. (He was acquitted). By the standards of today, the Baron’s photography of naked adolescent boys would surely have landed him in hot water. But in those days, he was seen as just another eccentric foreigner. He was generous to his models, and by all accounts liked by the townspeople of Taormina, where he was a local celebrity.

So, what does this tell us? It does not tell us that Sicilians were tolerant of sexual licence; rather it tells us that that they were tolerant of foreign eccentricity, and that Sicily was the sort of place where someone who found the cold north inhospitable could live comfortably and without scrutiny. There are other countries like that even today where discredited people from the north of Europe go to seek refuge, even though nowadays there is nowhere as tolerant as Taormina in the days of the Baron von Gloeden.

Writers and diverse as Dickens and Nancy Mitford may see Sicily as the land of the Lotus-eaters, but this says more about them than it does about the island. The Sicilians themselves in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries must have looked on the foreigners who came to disport themselves in the beautiful south with a mixture of puzzlement and wry envy, as people who unlike themselves were rich and leisured, and not preoccupied with the daily grind of making a living, which people, even in the south, have to do.

Has anyone written a novel about the Baron von Gloeden? Any such novel would be terribly dull: he evidently enjoyed his half century in scenic Taormina, with Etna on one side and the mountains of Calabria across the straits on the other, but he seemingly had his own way in everything, and self-indulgence does not make for drama or fiction. He is, to my mind, best regarded as a historical curiosity, and forgotten about.