Sicily’s most celebrated criminal was not a mafioso, but a bandit, the outlaw Salvatore Giuliano. Giuliano was born in Montelepre, a town not very far from Palermo in in 1922. He left school at the age of thirteen to work on his parents’ farm, but when he got bored of this, he took up the olive oil trade. When war came he became a trader in black market food (there were severe shortages of food all over Sicily, and the black market was what kept many alive.) One day, in September 1943, he was stopped at a police checkpoint and found in possession of two bags of contraband flour. Giuliano got away after shooting one Carabinieri and severely wounding another. He was twenty years old, and from then on a wanted man.

He died at the age of twenty-seven, in 1950, betrayed by the deputy leader of his band. During his seven year reign as a bandit king, he and his mates murdered numerous police and Carabinieri, and attracted growing national and even international attention. They made their living by kidnapping and robbery, while all the time, of course, acting like perfect gentlemen. During this time the Italian state threw increasing resources at the bandit and his band, but their repeated failures made them look more and more ridiculous; Giuliano became a hero, and remains one to this day.

At the end of the war there was a movement for Sicilian independence, and these separatists recruited Giuliano to their cause, making him the head of their private army, until the separatist cause fizzled out. The Mafia and various landed interests also decided to use him, and it was Giuliano and his men who attacked a May Day socialist meeting at Portella della Ginestra in 1947, which resulted in eleven deaths, which included one woman and three children.

Giuliano was a gun for hire, and he undertook these tasks in the hope of getting a pardon for his crimes. He was promised one by several important people, but one never came.

Giuliano was not a mafioso but the last in a long line of bandits who had at one time or another terrorised the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. There are several things that are very unMafia about him.

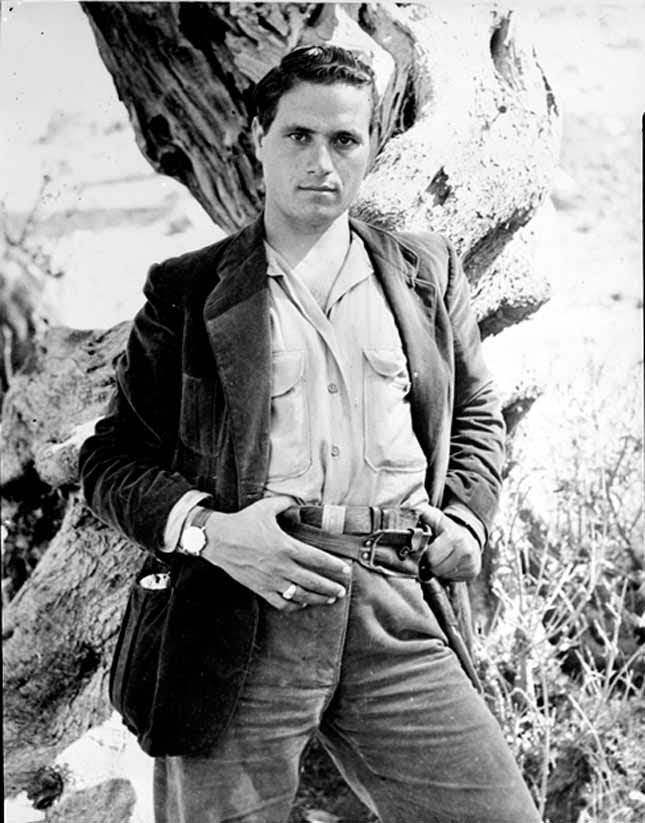

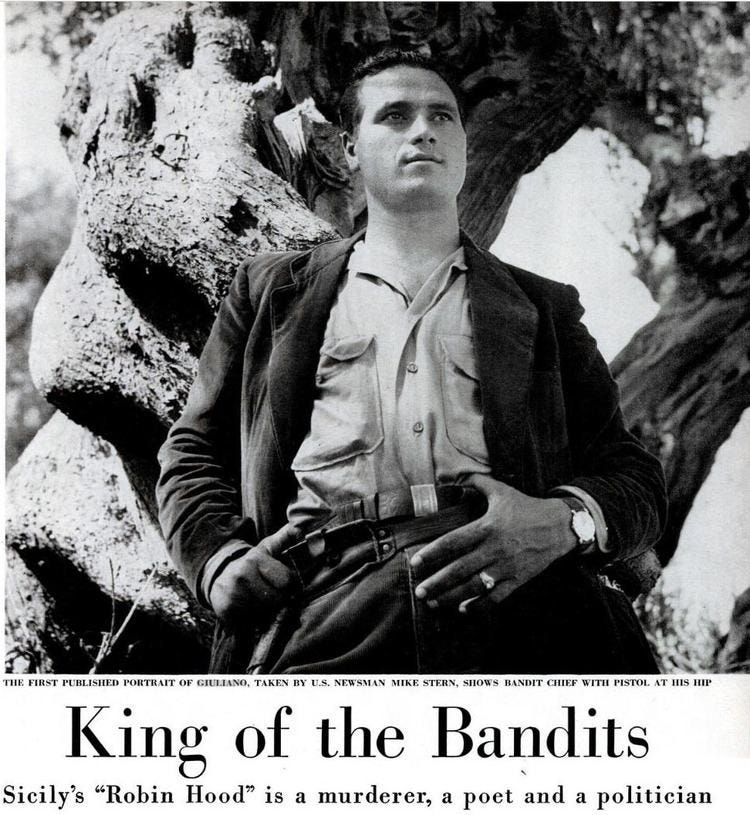

First of all, he courted publicity: several enterprising journalists made it up to his various hideouts and interviewed and photographed him. Giuliano was certainly vain, as a lot of good-looking men are, but he was also naïve, in that he thought courting publicity could gain him the pardon he coveted. He even thought, wrongly, that one of the journalists was an envoy of the US president. A real mafioso would realise that any sort of publicity was a bad thing. Totò Riina, who was on the run for decades, was only photographed when he was captured. No one knew what he looked like.

Secondly, and fatally in his case, Giuliano trusted the state and trusted those who were in power, and thought they would keep their promises and secure him the pardon he craved. Mafia men despise the state and distrust it. Funnily enough, so do many other Sicilians, and Italians more widely. His murder in Castelvetrano in 1950 was carried out by his deputy Gaspare Pisciotta with the connivance of the highest authorities in the Italian state.

But Giuliano tells us a lot about Sicily and criminality in general. He came from a poor (but not that poor, his parents were small landowners) background, and he posed as one who had the interests of the poor at heart. Surprisingly, this was taken at face value. He was on the side of ‘us’ against ‘them’, the anonymous ‘they’ who make life such a misery for the masses. He was a glamorous and romantic figure; that he defied the state for so long was a tribute to his resourcefulness, the support he found in the countryside around Montelepre, and to the supposition that anyone who ‘they’ were after must be a good thing. He was a Robin Hood figure, indeed the last of the Robin Hoods. He was a murderer, but it is very hard not to like him. He clearly wanted to be liked, and took care to hone his image. His public relations were tremendously successful.

His tomb is in Montelepre, and it is always decked with fresh flowers and candles. His mother and sister, who both adored him, have now gone to God, but the cult lives on. For his mother and sister, Salvatore Giuliano was the victim, of history perhaps, of circumstances, of the state, but for us today he is an emblematic figure of modern Sicily. There won’t be any more like him, thankfully, but he sums up a great deal of the island’s history.

‘Bored of’?