Sicily was notionally a separate Kingdom until 1816, when it was subsumed into the Kingdom of Naples to form the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Until then it had hardly been independent for hundreds of years. In fact, the old cliché goes that Sicilians have always been dominated by foreigners and the Mafia is their way of protesting about this.

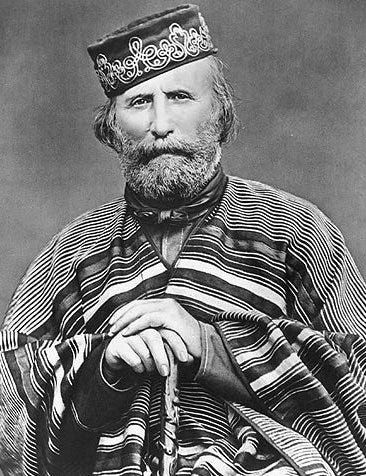

In 1860 Garibaldi and his redshirts landed at Marsala to help liberate the island from Neapolitan and Bourbon rule. But it needs to be remembered that Garibaldi landed in May, and the revolt against the Bourbons had already broken out in April. One cannot, tempting as it might be, see Garibaldi’s intervention as an invasion by foreigners, even if Garibaldi was from Nice, and his redshirts were from all over the world. The overthrow of the Bourbons and the unification of Italy was very much an international concern. Gladstone had described the Bourbon regime ‘the negation of God erected to a system of government.’ Palmerstone had made the Garibaldi expedition possible by not using the British Navy to stop it, which he easily could have done. And when Garibaldi landed, he encountered little opposition. There was a battle at Calatafimi, but otherwise the Bourbon regime collapsed before him.

The Bourbons of Naples, especially the final monarch, Francis II, who was very pious, and the son of the Blessed Cristina of Savoy, would have been perplexed to have his government branded as the negation of God, particularly by a Protestant like Mr Gladstone. He would have been offended too by the way an atheist like Garibaldi and a lecher like Palmerstone helped overthrow his Kingdom and give it to his Savoyard cousins.

The Bourbon government was not all bad. It is perfectly true that the south of Italy was infested with romantic looking bandits, but that was because there was no effective police force, part of the light touch Bourbon approach. There were no police because there were no taxes either; the state subsisted off customs dues. Taxes came later with the unification of Italy, and when they came were not popular, sparking off several revolts in the decades after unification.

The annexation of Sicily was approved by plebiscite but most people now agree these were rigged. The great Sicilian novel, The Leopard, mentions this in the third chapter. When his shooting companion, don Ciccio, tells him that he has voted ‘no’, whereas the whole of the town has supposedly voted ‘Yes’, the Prince understands that the birth of the Kingdom of Italy is in fact illegitimate, stained from the start.

At this point calm descended on Don Fabrizio, who had finally solved the enigma; now he knew who had been killed at Donnafugata, at a hundred other places, in the course of that night of dirty wind: a new-born babe: good faith; just the very child who should have been cared for most, whose strengthening would have justified all the silly vandalisms. Don Ciccio's negative vote, fifty similar votes at Donnafugata, a hundred thousand "noes" in the whole Kingdom, would have had no effect on the result, would in fact have made it, if anything, more significant; and this maiming of souls would have been avoided.

There is a lovely illustration of the benign neglect under which Sicily lived in the Bourbon times in the museum in Trapani. This is the guillotine. It dates from 1800 and seems to be in perfect working order; one is surprised to find it there, and surprised by the date, as the Queen of the Two Sicilies at the time, Maria Carolina, had some seven years previously just lost a sister and brother-in-law to the guillotine. But while we look upon guillotines and think of the Terror, in those days they were seen as signs of Enlightenment, being more humane than many of the forms of execution they replaced.

The Trapani guillotine is unusual in that all the parts are numbered. It was meant to be mobile, to travel Sicily dispensing justice, and to be assembled where it was needed. It is clearly a top of the range instrument; one notes the basket for catching the head, and the coffin beneath for the headless corpse. The most astonishing fact, though, is that it was only used twice, both times to decapitate brigands. This hardly accords with the idea of the Bourbon state being a bloodthirsty tyranny.

But while most Sicilians must have welcomed Italian unity, the myth that Sicily was handed over to just another foreign overlord, this time from Piedmont/Sardinia, has some basis. Modern Sicilians, at least in my imagination, refer to what lies beyond the Straits of Messina as ‘Italy’ or ‘the continent’, a foreign land. They see themselves as separate, apart, a differing if not entirely different nation. Moreover, and this is something I have witnessed on several occasions, Italians from the north refer to Sicilians sometimes as foreigners and even ‘Arabs’. There is plenty of anti-Sicilian feeling in northern Italy.

The unification of Italy is a project that has never been completed. The Mafia is primarily a money-making enterprise. But if one wants to consider it imaginatively or even romantically, one must consider it as an organisation that defends national, that is, Sicilian, pride.