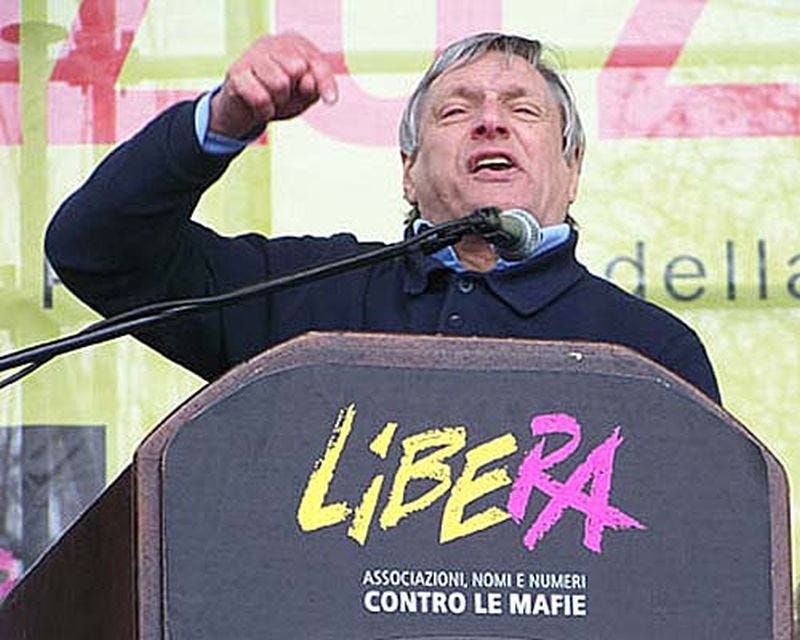

There is a very interesting article in the Sunday Times this week about organised crime in Italy. It deals with the work of don Luigi Ciotti, a saintly Italian priest, now 79 years old, who had dedicated his life to helping the disadvantaged. One project he founded is called Libera, which aims to free women who are married to Mafiosi and wish to escape the life of being connected to gangsters.

The article tells the story of Anna, naturally not her real name:

“After seven years of marriage Anna had become used to her husband’s unexplained absences. The son of a powerful figure in the ’Ndrangheta, the ruthless Mafia organisation that holds sway in Calabria, the toe of Italy’s boot, he often had “something to do”, and she knew better than to quiz him about what that something was.

“You couldn’t ask where he was going,” she says. “On the surface it all seemed normal, but at the same time he was living another life. There were certain things women did not get mixed up with.” It had been the same when she was growing up: their families were connected and her own father was also in the mob, albeit in a lowlier position. Her mother, too, had always spared him awkward questions.

That evening in September 2008 felt different. Anna was working late in the local restaurant and was surprised to hear her husband had failed to drop by her mother’s house to pick up their three young daughters, then aged from nine months to six years. “I called her at eight and then every hour until midnight and he still had not come,” she says. “When I finished work at 1am I got the car, went round to my mother’s, picked up my daughters and took them home.”

When there was still no sign of him the following morning she began to worry. Over time it became clear to her that her husband had been killed — and that his murder had been ordered by members of his own family. All these years later his body has still not been found.

“They call it a lupara bianca,” she says —literally a “white sawn-off shotgun”, a mafia tradition according to which the remains of those who break the rules of the family are buried in the concrete pillars of bridges, dissolved in acid or dumped in the sea.”

Thanks to don Ciotti and his organisation, Anna was able to get way from Calabria and eventually have a new life. She did not know anything that would have been of use to the police, so she was not taken into witness protection, but nevertheless she was in danger, and had several narrow escapes. The Mafiosi can never let someone go. The whole organisation depends on coercive control, both of the men and the women. There can be no escape from the boss, because to escape the boss is to prove that he is not all-powerful, and the myth of omnipotence is what keeps the boss in business. Moreover, on a sort of mystical plane, how can you have ‘another’ life, when the life of the Mafia is the only life there is, or at least the only life worth living?

I find it very interesting that Anna was the daughter of a Mafioso and married to one as well - that was her world, a closed world. She was certainly brave to break out of it. She lived in a world where women did not ask questions, which is quite something, considering how much any human being desires to know. Not to ask your husband anything, ever, must be quite a feat. It is the same in the The Chemist if Catania where the eponymous character is frequently absent, but his wife never asks what he is doing. Her desire not to want to know goes to extraordinary lengths, as with real-life Anna, who is supposed not to question the disappearance and murder of her own husband, the father of her daughters.

The world of the Mafia has to be a closed world, because reality has to be kept at bay, because if it broke in, the magic of the Mafia would dissipate (the world Mafia is derived, it is thought, from a word that means something like glamour, the magical mist that descends in the highlands.)

Obviously Anna’s relatives could not let her go. To be defied by a woman would be shaming. But it goes further: if the women start to defy you, it would only be a matter of time before the men did, once they realise you can be defied. In addition, the women are the ones who provide the structure of the clan movement, which is partially strong in the ‘Ndrangheta. They are the links between the men, the ones who maintain the web of kinship. The Mafia is incestuous in all senses: you marry someone you have known all your life (as in Anna’s case) and she is is more likely than not a relative by marriage or even a distant cousin. For the family to remain strong, you need to keep it in the family. Marrying an outsider (which in ‘Ndrangheta terms would mean someone not from Aspromonte) would be to invite trouble. When Anna ran away, her clan must have been most disappointed in her. They thought that they knew her, that she was una brava ragazza, a good girl….

Don Ciotti is a social and Catholic activist, and his approach is based on action not words. If all the women were to come out of Mafia families, the Mafia would collapse. No wonder the good Father has a bodyguard. The Mafiosi must see him as a real threat to their very existence.