Just who are the mafiosi? By which I mean, what sort of people ‘work’ for the Mafia? And what sort of work do they do? The answer may surprise and shock you.

Thirty years ago, I was in the Spanish Quarters of Naples, the historic centre, known also as Spaccanapoli (literally ‘Splitnaples’), bounded by the narrow streets of via San Biagio dei Librai and via dei Tribunali, which follow the ancient Roman roads. This was a very exciting place to be: the streets were squalid, picturesque, and they teemed with life. It was winter, it was dark, and the place thrummed. It was a world away from the staidness of Rome.

As was not unusual at the time, there was a strike in Italy: this time it was the tobacconists. This was seriously bad news. It means that nowhere in the country could you buy cigarettes. People were actually doing ‘fag runs’ all the way to Switzerland. But in Spaccanapoli, standing at street corners, were little boys holding packets of unopened cigarettes. Money was changing hands. I approached a little boy, and asked him if he had any Benson and Hedges. This puzzled him, as he had probably never heard of the brand, and why should he? But he politely said he would ask, and ran off, before I could stop him. Within five minutes, he returned with a shiny gold pack of B and H. The price was well below the market value; this struck me as an opportunity too good to miss. I asked him if I could have a carton of 200, a stecca (a ‘stick’). He scampered off and returned with what I had asked for; I paid and walked off with the carton under my arm feeling very pleased with myself. Not only had I saved money, I had got enough cigarettes to see me through the strike.

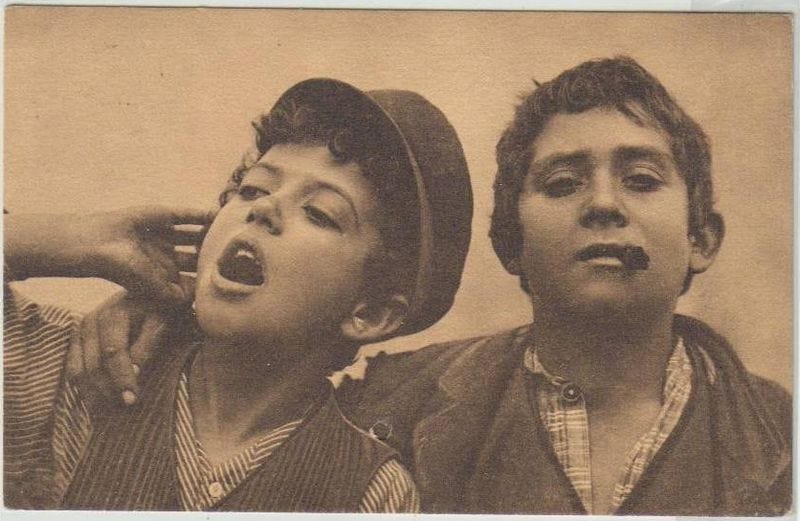

I was later told that I ought to have been arrested for handling contraband, and that if the police had been doing their job, I would have been. Contraband cigarettes, that is those sold under the counter, untaxed, not controlled by the state monopoly, were illegal and their trade the main source of income of the Camorra, Naples’s organised crime. One usually assumes that drugs are the biggest earner, but cigarettes, smuggled in from the Balkans, were in fact the main money spinner for the Camorra, at least in those days. And the police could do nothing about it, because the sale of such goods was handled by little boys all under the age of ten, under the age of legal responsibility and thus immune from arrest.

So, if you want to know what the average mafioso is like, he is quite likely to be a very young boy (always a boy, never a girl). The Mafia runners are children, who then, having won the trust of the organisation, move onto other things, such as bag-snatching, and, once upon a time, breaking into cars to steal radios, when that was a profitable activity. Now the more profitable thefts would be mobile phones and wallets. After that the teenage criminal moves on to extortion, beatings and murder.

English literature’s most famous gangster novel is Brighton Rock, whose anti-hero is Pinkie Brown, aged seventeen. Greene emphasises Pinkie’s physical immaturity (he does not shave) and emotional stuntedness (he is not interested in sex at all, and holds Rose, whom he marries, in hatred and contempt). Naples, thirty years ago, was full of boys years younger than Pinkie, earning pocket money from the Camorra; and there must have been many a Pinkie Brown as well, seventeen year olds who had seen more of the seamier side of life than many an old man. Greene’s characterisation of Pinkie as an old ruined soul in a barely nature body is astute.

One thing that has changed since I was quite innocently buying contraband from the Mafia in Naples is the arrival of the internet. Criminality leaves a money trail behind it; cash cannot be traced but it has to be ‘washed’; criminality leaves an electronic trail behind it too. Clever policemen can read computers and tail criminals without ever leaving their desks. But if criminals do not use computers or phones, what then? They become impossible to trace. There are no tell tale emails, no phone signals to give them away. But how then do they communicate with each other? Easy – whispered conversations with nothing entrusted to paper, and messages passed verbally by little boys who cannot be arrested by the police. Naples swarms with little boys who aren’t at school. So does Palermo, so does Catania. That boy who sold me those cigarettes decades ago planted another seed for fiction in my mind.