There is a nice article over at The Spectator by the great and good Nicholas Farrell, which discusses The Leopard, the great Italian novel, which is now being dramatized on Netflix. Farrell says, quite rightly in my opinion:

“The Leopard is an exquisite meditation on death – the death of the Sicilian aristocracy and of the prince himself. He does not resist the risorgimento. He does not try to combat fate, destiny, or fortune. He accepts that his time has come.”

The novel and the Visconti film are brilliant evocations of decline, and wonderful tributes to the genius of Sicily, whose greatest ages was almost a thousand years ago. If you have not seen the Visconti film, please watch it now. It’s a masterpiece.

Farrell also makes a point that has been made before:

“But it is also about the Mafia, even though the word is never uttered (Angelica’s father is clearly a proto-Mafioso). It is precisely at this moment during the reunification of Italy between 1860 and 1870 that the Sicilian Mafia – Cosa Nostra – is born.

Under the ancien régime, the aristocracy had kept order. Now, no longer. The Mafia began in Sicily because the ‘piedmontesi’ from Turin who had driven Italian reunification castrated the Sicilian aristocracy but were themselves hardly present on the island. The Mafia exists because the state is absent. The Mafia fills the vacuum. It becomes the state. And if necessary it will feed you to the pigs, or drown your son in acid.”

Indeed. The book is set at the time of the Risorgimento, which promised much but failed to deliver. In Sicily this failure was particularly marked. The modern democratic state was stillborn, and the Mafia filled the vacuum. As I have mentioned elsewhere, Sicilians understand the Risorgimento as something they did not choose, but which was foisted on them by fraud - in particular fraudulent plebiscites.

But there is something else at work. The old Sicily of the Prince of Salina was very beautiful; Visconti’s film and Tomasi’s novel are both sensuous experiences. You really do feel you are drowning in honey. Sicily may be in decline, but its beauty makes you forget the modern world; and Claudia Cardinale, as Farrell points out, makes you forget everything except herself.

Farrell says:

“Yet there are so many similarities between Tomasi’s The Leopard and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather. Prince Salina and Don Corleone are both so very princely. Martin Scorsese, whose family are from Sicily, has said of Visconti’s The Leopard: ‘I live with this movie every day of my life.’”

The modern Italian state, born in 1860, what we call Liberal Italy, was an ugly and uninspiring thing: pompous, self-important, full of bluster, which produced nothing of artistic value. If you do not believe me, contemplate the Vittoriano in Rome, the monument to Italian unity and Victor Emmanuel II, popularly called la macchina a scrivere (the typewriter) in Italian, known to us English-speakers as the Wedding Cake. It is supposed to revive the glories of ancient Rome. It is a piece of architectural rubbish, reminiscent of the film set of the blockbuster Cleopatra.

Less bombastic but almost worse is the Piazza Vittorio Emmanuele, on the Esquiline in Rome, supposed to be reminiscent of the elegant arcading of Turin. It is rundown, hideous, jerry-built crap. It replaced a beautiful vine covered semi-rural district.

By their architecture shall you know them. No wonder people, longing for the princely rulers of the past, cottoned onto the Mafia princes, rather than the new rulers from Piedmont. The Mafia was local (a huge selling point) and the Mafia had class and glamour. Don Corleone is so very princely, as Farrell observes. By contrast the royals from the north looked like buffoons.

There are of course two trends in the Mafia. One lot of bosses have dressed like peasants, to emphasise their man of the people credentials. The scene where don Corleone dies in his gardening clothes reminds us of this. But at his daughter’s wedding he does look great - well, he is played by Brando, so what do you expect? More recently, in America and in real life, we have had the very smart John Gotti, known as ‘The Dapper Don'. While it is true that both don Calogero Vizzini and Salvatore Riina both looked like slobs, in my own work I have tried to emphasis the ‘dapper don’ vibe. Italians love il bello: when I lived in Italy one would always hear praise for Tony Blair’s clothes and good looks. No one cared about his policies at all. Looking good is an exercise in Mafia public relations. God forbid you should be the opposite of bello, that is brutto, though I suppose it did not hold back Vizzini or Riina.

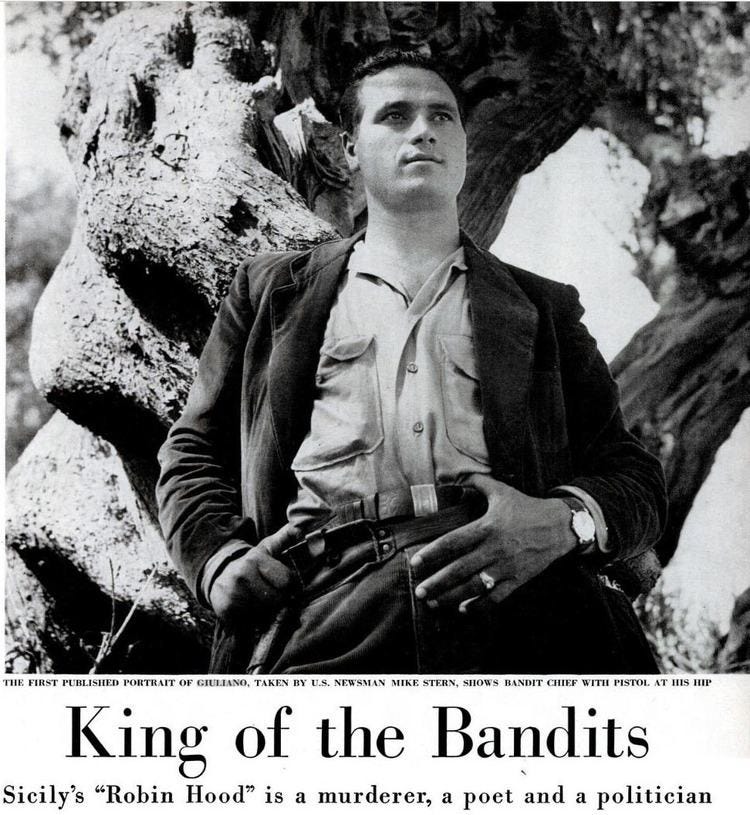

When I visited the tomb of Salvatore Giuliano in Montelepre, the cemetery manager said to me, without being prompted: ‘He was a beautiful man, wasn’t he?’ In the end, for some, that is all that counts!

Regrettably both Il Gattopardo films miss out the conclusion of the novel, which is a great pity since it brings the reader face to face with the aftermath.

Is there a concordance of cross-references between "Il Gattopardo", the Godfather films and the "Chemist of Catania" novels? Or is it my next project? Perhaps I should spend a couple of months at Donnafugata conducting research.